Did you know that consumers return about 20% of the products they purchase online? Online return rates have significantly increased over the years, and they’re especially high compared to in-store purchases. In fact, online return rates are often two to three times higher than digital (in-store) return rates.

According to research from Capital One, in 2024 alone, consumers in the U.S. returned around $362 billion worth of merchandise from online sales.

But how exactly are these refunds processed behind the scenes?

Before 2021: Refunds Were Simple—but Risky

Prior to 2021, processing refunds was fairly straightforward. Merchants could simply push refund transactions back to customers’ bank accounts without any prior authorization from the card issuer.

However, this approach had significant drawbacks:

- Lack of visibility for customers. Many consumers had no way of knowing whether the merchant had actually initiated the refund.

- Fraud risk. Fraudsters could exploit the system to push credits to unrelated cards, launder money, or create other financial abuse.

- Delayed processing. Refunds often took 2–3 business days, leading to confusion and increased calls to merchants’ customer service centers.

Let’s examine how refunds impact payments, risk, and customer experience, comparing before and after the introduction of refund authorization mandates.

Refunds: Comparing Before vs. After Refund Authorization

| Aspect | Without Refund Authorization | With Refund Authorization |

|---|---|---|

| Payments | Merchants could easily process refunds without issuer approval. However, if the card account was closed, the issuer had to figure out how to handle the refund. This only worked if the customer still maintained a relationship with the bank. If the customer severed the relationship entirely, the issuer might either return the refund to the acquirer or leave the payment in limbo. | Merchants must first run a refund authorization. If the authorization is successful, they proceed to send the refund to the customer’s account. If the authorization is declined, merchants can reach out to the customer for an alternative card, issue a check, or offer store credit. |

| Payments Risk | Several fraud scenarios existed: 1. Fraudulent Credits to Random Cards: An employee colluding with fraudsters could key in a refund to a card that never made a purchase. 2. Money Laundering: Fraudsters could use refunds to “clean” illicit funds by buying expensive goods and refunding them—sometimes even to different cards. 3. Refund Flipping: A fraudster makes a legitimate purchase, disputes it, and demands a refund. They collect both the chargeback and keep the goods, resulting in a “double dip” fraud loss for the merchant. | The issuer can verify whether the card was used for the original purchase, check for suspicious activity, and decline transactions to random cards or known refund abusers. This protects both genuine customers and merchants from fraud. |

| Customers | Without refund authorization, customers often had no visibility into the status of a refund after the merchant agreed to process it. If a card was closed due to loss or fraud, customers had to rely on the issuer’s best efforts to receive their money. Even if the merchant offered to issue a check, there was no guarantee, leaving customers confused or even financially stranded if they had severed their relationship with the bank. | With refund authorization, as soon as the merchant runs the refund authorization, the customer can see a pending credit on their card. If the transaction is declined, merchant customer service teams can assist the customer by offering alternative options like a check or refund to another card. |

Important Note

Refunds and reversals are not the same thing.

- Refunds apply when the original transaction has already been settled (i.e. the funds have moved from the customer to the merchant).

- Reversals or voids happen when the customer cancels the transaction before settlement—the funds never leave the customer’s account.

In this article, we’re focusing specifically on refunds.

Refund Authorization Declines

Just like regular purchase authorizations, refund authorizations can also be declined. Industry estimates suggest that 6% to 10% of refund authorizations get declined, depending on the quality of the cards involved in the original transactions.

Common decline reasons include:

- Account Closed

- Invalid Transaction

- Transaction Refused

- Invalid Account Number

- Transaction Not Permitted to Cardholder

Don’t be surprised if you see vague responses like “Insufficient Response” on a refund transaction. Sometimes issuers suppress the true reason for a decline for security or privacy reasons, or technical issues may occur on the issuer’s side.

What Should Merchants Do If a Refund Authorization Is Declined?

Both Visa and Mastercard recommend that merchants handle refunds manually in such cases—for example:

- Issuing a check to the customer.

- Providing store credit for a future purchase.

What Happens if a Merchant Sends Refunds Without Authorization?

If merchants skip the required refund authorization, they’re subject to fees from the card networks:

- Visa: Charges $0.10 for every refund transaction submitted without authorization.

- Mastercard: Charges a Processing Integrity Fee ranging from $0.04 to $0.25, depending on the region and program.

Many merchants choose to perform refund authorizations to avoid these fees. However, some continue paying the penalties because they don’t want to invest in manual refund processes like issuing checks.

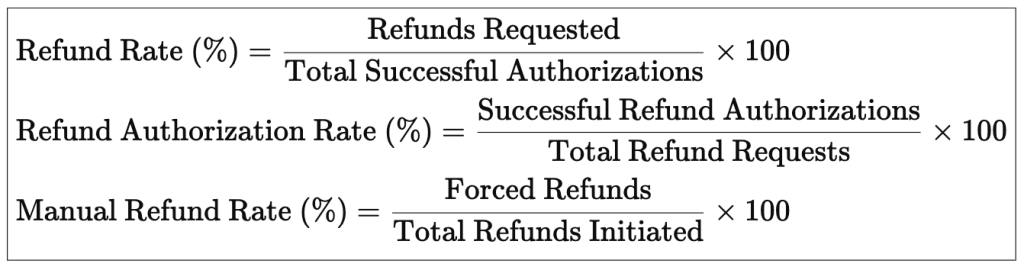

Key KPIs for Refund Authorization

Refund transactions often don’t get the attention they deserve. However, as discussed, they can signal underlying fraud trends. Regular monitoring helps mitigate fraud risk and keep merchant accounts (MIDs) healthy for normal payment processing.

Important KPIs include:

Stay tuned for my next post: How to Implement Refund Authorizations.